Splitting Hairs or Splitting Heads: The Semantics of Violence

There is nothing sexy about beating a man to death with a claw hammer.

Okay, let’s rewind a little bit. Once upon a time I had two very different (and yet not so) conversations about what it is that we do. The first one involved a grandmother and her very young grandson who just happened to be walking by class while we had the big door rolled up. She looked extremely uneasy, the child even more so.

“What is this?” she asked, eyes wide.

“It’s the intelligent use of violence as a survival tool,” I replied.

“Like self-defense? Like when you’re in trouble?”

I hesitated. I wanted to say “No, more like breaking people,” but she had asked with such hope in her voice, as in, I sure do hope this isn’t what my gut is telling me it is—please reassure me. So I blinked and let it go.

“Yes,” I said, “it’s exactly like that.”

Her face flushed with relief. It wasn’t what the awful knot in her gut said it was. These were sane people after all.

The second conversation occurred at my (then young) son’s weekly piano lesson. It turned out that I went to high school with one of the teachers, and when he realized this he googled me to see what I’d been up to for the previous 20 years.

“So, you’re still doing that martial arts thing?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I nodded, “but it’s not martial arts anymore.”

He frowned. “So it’s like self-defense?”

“No—more like beating a man to death with your bare hands.”

His eyes widened and heads began to turn. The metaphorical needle came off the record and the chatter in the room dipped a bit as people began to tune in to our conversation.

“But you don’t use any weapons.”

Once again, the hopeful inflection in the voice. He wanted me to veer back into something sane, and away from the idea of killing.

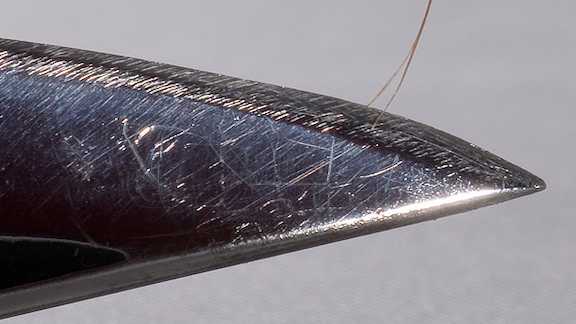

I didn’t blink. I gave it to him straight. “Sure we do—you can beat a man to death with a claw hammer or stab him to death with a kitchen knife. It’s all the same.”

That did it. Everyone in the room was listening now. Everyone had questions, and every single one of them was to try to get me to recant, to box me into a corner where I’d have to admit that what I meant was a sane, righteous, defensive use of force to disarm or disable an “attacker”—not the wonton misuse of power to maim, cripple and kill at will.

I was my usual courteous, approachable, informational self—but something told me that future conversations at music class would be strained. Maybe I should have told them it was just kung fu.

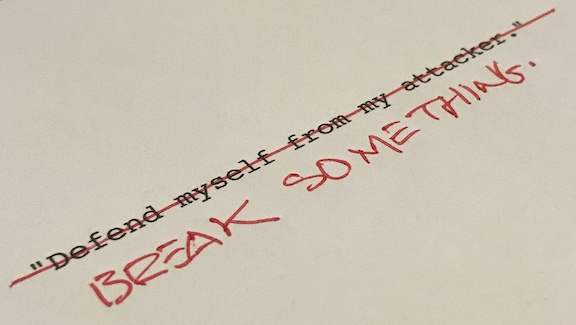

Often, when I’m attempting to explain what it is we do, I’m accused of splitting hairs, told that it’s “all just semantics.” That one person’s self-defense is another person’s claw hammer murder. But the ridiculousness of that sentence shows it ain’t so.

I’ve written previously about how socialized people like to fall back on euphemisms to distance themselves from the ugly, brutal reality of what has to happen in violence—namely you seriously injuring another person. Not stopping when they beg you to stop. Not interacting with them as a person, or even an enemy, but as meat to be torn to uselessness.

Describing it in these terms causes (dare I say) violent reactions in lay people as they instantaneously judge you to be adrift without a moral compass, operating at the debased level of the criminal sociopath—in a word, insane.

People parse killing in socially acceptable terms (martial arts, self-defense, etc.), to show other socialized people that they are not “bad”. When someone defies convention and steps out of bounds (“beat a man to death with a claw hammer”), the strong reaction comes from an unconscious, intrinsic understanding that if everyone’s playing by the same rules, we’re all okay. And as soon as someone decides not to, we, the people who play by the rules, are royally fucked.

This social parsing of violence then takes the next step up to seize the moral high ground where we all have permission to behave badly. Witness the “attacker/defender” dichotomy. If you are the defender, you are cleared hot, in pretty much everyone’s mind, to brain the attacker.

The moral high ground is also a cool place to be seen. There you are, on the wind-swept mountain top, beams of blinding righteousness radiating from your head. It’s super-sexy with a double side order of pizzazz. Having a black belt in martial arts impresses friends, and whatnot. Knowing how to kill a man is less cool in most circles. Being ready and willing to do so is another thing entirely.

Maintaining righteousness in the face of simple killing takes a lot of mental gymnastics. Many people advance schema using Animal Farm-esque stand-ins to try to illuminate the roles to be played. White hats and black hats. The protectors and the helpless. Guess what? Those are nice lies we tell ourselves to feel better about what it is we’re training to do.

There is no animal schema, no predator and prey, regardless of which one you think you are.

There are only naked humans, milling about on an infinite gray plane. You’re one of them, and everyone else is stuck in there with you. We all have the same set of advantages and disadvantages. Identical physical constraints and powers. We each possess the most dangerous weapon in the known universe, a human brain.

Everyone, exactly the same on a level playing field. Not comforting in the least, but then, when was the last time reality was comforting?

So how do we talk about it? Let’s look at some of the most common terms, and then I’ll toss mine in. And I promise it’ll be a live psychic grenade.

Martial Arts

This really only works in the ancient Greek sense, as in “the skills required by warriors to make war.” This sense has been completely lost in the modern day (think of the Olympic Decathlon), and I doubt anyone out there thought of “maintaining and operating a cruise missile launcher” when they read the words “martial arts”. More likely than not you thought of your local karate school. And until that kind of training is necessary for serial killers to ply their hobby, it will remain a misnomer for what it is we do.

Self-Defense

This is the next logical step. And yet, “beating a man to death with a claw hammer” tends to strain the definition of self-defense beyond the breaking point. Self-defense requires an attacker; it requires you to be second banana in physical terms (as the lowly, yet much loved defender), but don’t sweat it. ‘Cuz you’ve got the moral high ground, and that awful attacker had no right to be doing these things to you. Good luck, and remember this comforting fact: you are in the right no matter how it all works out.

Beating a man to death with a claw hammer probably isn’t allowed in self-defense, but—funny how the universe works—it may be just the thing that has to happen in order for you to survive. When given the choice between self-defense and survival, let’s all pick survival, shall we?

Fighting

This doesn’t work because it’s too wide open. You can fight with your sibling, your spouse, your boss. On the high end you can fight for your rights; on the low end you can fight for the TV remote. Do any of these uses make you think of stabbing someone in the neck? (I mean other than the TV remote one.)

Fights can have rules and referees. Murders don’t.

Combatives

No. Just no.

Hand-to-Hand Combat

Here we are—down to the hard-nuts, in your face, XXX-TREEEM!!! term. While on the surface it would seem to be the one we want, it’s still somewhat lacking. Hand-to-hand carries with it the connotation of back-and-forth, tit-for-tat. Most people would not readily apply the label to a man being beaten to death with a claw hammer. The question you have to ask yourself is: “Do the people who are best at violence in our society (the criminal sociopaths) truly engage in hand-to-hand combat?” I’ll let you answer that for yourself.

So, what is it we do? What words can ever truly communicate the essence of it?

At a seminar someone asked a foe-specific question about an extremely accomplished combat sports champion. This champion is big and tough and skilled. The question was, “How would you defeat so-and-so?”

To which I replied, without hesitation, “I’d start by hiring someone to shoot his dad.”

And that’s it exactly, rendered as precisely as words will allow.

— Chris Ranck-Buhr (from 2005)