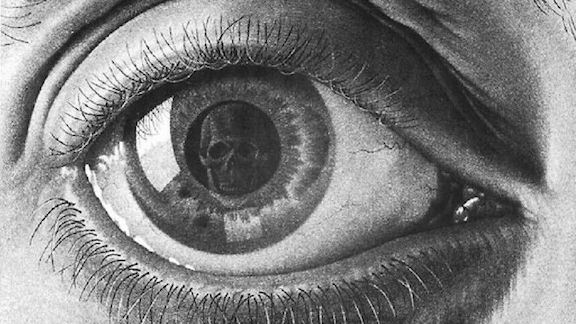

Treat Everyone Like They’re Six Seconds Away from a Killing Spree & Other Philosophies of Good Neighborliness

“Violence is the last thing I want to do, but it’s the first thing I will do.”

— Master Matt Suitor

Does knowing how to use the tool of violence inform your relationship with your fellow human beings? There are really two angles to come at this question from: knowing what violence entails (or “means”) and knowing how to get it done.

In terms of knowing what violence entails, i.e., the terror and ugly finality of it, the trend is clear: intimate knowledge leads directly to avoidance. The more one knows about violence, the less eager one is to get involved in it. Resolved, yes—eager, no.

This has a great deal to do with the narrowness of the tool, the fact that violence only does one thing: it shuts off a human being. The vast majority of your daily social interactions do not require this. It is unnecessary, therefore, to push social interactions in directions that could result in violence. Personally, I found I’m much more likely to capitulate and disengage by leaving the area, without a word, when confronted by someone with an obvious chip on their shoulder who has chosen me as the knock-off guy. Everybody wins—I sleep well, and neither of us gets a broken leg just because he was having a bad day.

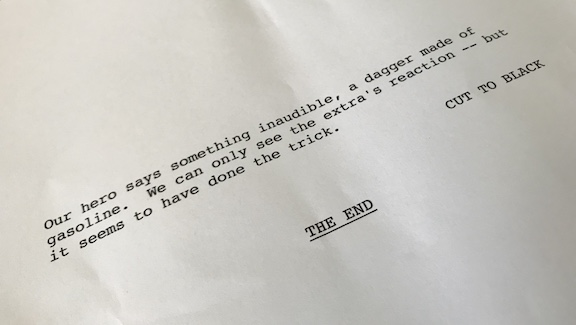

My brother, Tony, tells a hilarious story in which a man accosted him by saying “Let’s fight!” and punching him (ineffectually) in the head. Tony thought about what that would mean—he saw himself breaking the guy’s leg and stomping a mud hole in him on the ground, and thought to himself, He can’t want that. So he said no. The guy persisted, again asking for a fight and punching Tony. Finally, my brother had it and shrugged, thinking, I guess that’s what he wants, and proceeded to make the guy’s head and feet trade places with a single strike. It wasn’t so much a “fight” like the guy was asking for as it was a “single man-stopping injury.” Tony knew that’s where it would go (and more importantly, that it could go either way); knowing how serious it was made him uninterested in going there recreationally—if he didn’t have to, he didn’t want to.

I find that I am possessed of a saintlike patience these days—somehow, somewhere, I developed the habit of giving pretty much everyone the benefit of the doubt. I do not begrudge those who are curt and prickly their public anger and annoyance. I just figure there are extenuating circumstances I’m not aware of and I have no desire to be the next point on the down-trending curve of their bad day. I do my best to treat everyone with patience and respect—and how is that different, really, from treating everyone as if they were six seconds away from a killing spree? I’d much rather be the control rod in the nuclear reactor than the ignition charge in their personal H-bomb.

This gets us to the second angle—beyond mere knowledge of violence and into confidence in how to get it done. Nietzsche said that courtesy comes from a position of power; I would say it comes from both the knowledge of, and confidence in, violence. Politeness flows from a desire to avoid violence coupled with the knowledge that if worse comes to worst, the skill is literally in the palm of your hand. Socially, you have nothing to lose. Rude people fear that courtesy is a sign of weakness, that something is taken from them when they wait their turn or let someone else go first.

Knowing how to get it done removes the uncertainty from the extreme end of the scale—the answer to “But what if he goes off?” is “I’ll break his leg and stomp a mud hole in him.” And so I find myself in the position of being resolved, but not eager. If I don’t have to, I don’t want to. If I have to, I will.

— Chris Ranck-Buhr (from 2007)