How many times have you rehearsed your attempted murder?

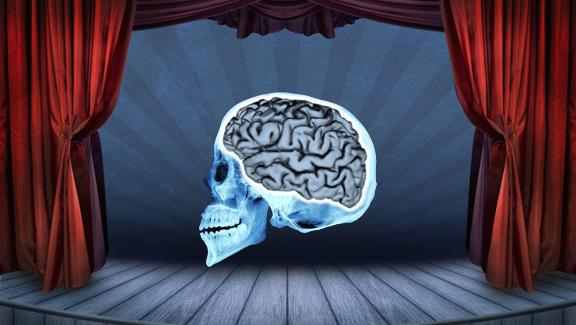

The brain can only go where it’s been before.

When it comes down to it, all you will have during your attempted murder is your experience — not your motivation, your strength, or even your training — the only thing you’ll have is what you’ve done with your own hands in front of your own eyes.

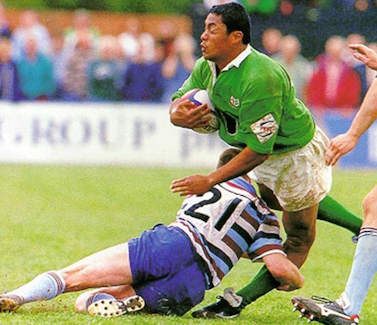

Experience is not the same as information — you can watch all the videos on rough water swimming you want, you can talk about it and read about it for hours and days and weeks — but none of that is going to matter when you actually hit the water. In that moment you’ll either swim or drown, and your success depends a great deal on how much time you spent actually doing the thing required to survive.

When we teach the use of violence as a survival tool we start with information — defining violence, describing actions and results, modeling movement — and then show you how to convert that information into knowledge: your ability to do it yourself. But even that’s not enough. When the time comes you won’t remember what we said or even what you know on a conscious level. All you’ll have is what you’ve done.

That’s where the hours on the mats come in. Our goal in a 2-Day Crash Course is to get you to execute a thousand turns — that’s a thousand times you recognized a threat, made a decision about how to destroy it, and then executed on that decision to end things in your favor. It’s rehearsing your attempted murder a thousand times — with knives and batons and firearms and grabs and holds and chokes and multiple people — so that if, God forbid, you ever find yourself there it won’t be the first time. You’ll be experienced… and therefore much more likely to get it right once more.

All those hours on the mats, doing serial target practice on the human machine, shattering anatomy one piece at a time, is where you will convert your knowledge into experience. This is the most powerful learning, and something we can’t do for you — only you can do it for yourself. We can show you what to do, and how to do it, and help refine your process as you convert knowledge into experience, but ultimately you’re the only one who can show yourself how you get it done.

A common refrain we hear at the start of the second day is “I don’t remember what we did yesterday!” And yet… when they step out onto the mats they just start doing. This is by design. What they mean is that they’re looking back through their declarative memory and finding it weirdly blank — they know they “learned stuff” yesterday, but they can’t recall precisely what in a specific, ordered sense. But that doesn’t matter, because the fact that they can step out onto the mats and just do it means that the experience of their 500 turns on that first day are firmly embedded in procedural memory — the place where walking and swimming and riding a bike are stored. The booby trap has been installed, the pit dug, the spikes set, the springs wound tight. And the whole thing covered over and smoothed out so it looks just like unturned earth.

They’ve weaponized their skeleton. It will be there for them, stealthily locked and loaded, for the rest of their lives.

What about you?

— Chris Ranck-Buhr

Our last 6 Crash Courses have been for private groups — but now that our schedule has opened up, we can offer this training to you!

Come learn an enduring life skill!