Disclaimer

There are serious legal and moral problems with injuring someone who isn’t trying to injure you or hasn’t otherwise threatened you with serious harm or death. For the sake of this discussion on the idea of the sucker punch, or otherwise taking people out from behind or when they don’t know it’s coming, we’re going to assume you are right to do it—that your impression of the situation is such that you believe inaction on your part will get you (and/or others) seriously injured or killed.

To injure or not to injure?

We all know what to do when someone comes after us—get in there and cause an injury, then repeat until satisfied. But what if the person hasn’t crossed the line physically, but has let it be known to you, overtly or not, that violence is in the offing? This is everything from a hijacker telling you to sit back down on an airplane, or a mugger making his demand, “Give me your wallet,” and all the way down to a simple, “You’re not leaving,” as you try to go out the door after a party. You may stand there a split second, taken slightly aback by the seemingly social interaction—he spoke to you with arms crossed, rather than hitting you, or even cocking back to hit you, or even laying hands on you at all.

Now what?

This is where the judgment call starts. If you decide to work it out with social tools, then go for it. I wouldn’t recommend it with the hijacker, the mugger could go either way depending on your personal read of the situation, and the jerk at the party is even less clear-cut.

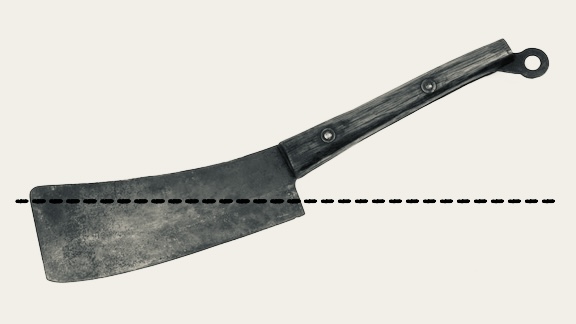

If you want to go physical and start injuring them, it’s best to dive in and get it done as soon as you make the decision. Waiting around to see how it develops gives the other person more traction, control, and confidence over the situation—this is how one man with a blade can take over an entire room full of people. The longer it goes on, the more in charge he is. If you take him as soon as you realize it’s a bad situation, he never gets the opportunity to assert social dominance. For any kind of hostage-taker, the most critical portion is first contact with the potential hostages. This is where he’ll either get everyone to capitulate, or it’ll all go to hell for him. It’s your job to punch his ticket and get him to tell Charon you said hi.

Let’s backtrack a little and take a look at the realities of violent conflict for the average law-abiding taxpayer. In all reality, you’re probably going to be the one getting sucker-punched. Because you’re not out looking for it, on the hunt, prowling for victims, you’ll typically know it’s on because someone is trying to do it to you first. Your part in this is easy—if you can still think and move, you’ll crush their groin or gouge their eye (or maybe some of both). Anecdotally, this is how it goes: “There I was, minding my own business, when this guy comes out of nowhere and punches me in the head.” The next part is about looking at a target and wrecking it. “So I look up from the ground and see his knee as he’s stepping in and I rolled into him and broke it.” The rest you know. Or at least can guess. (They survived to tell their version of the story, after all.) This is how it will probably come to you: Out of the blue, when you’re sick or tired, or otherwise encumbered, when you least expect it—almost by definition.

When you’re walking around with your head up, bristling with confidence, you send an unconscious message. When you walk like you know how to break a leg, predators read it and go looking for the stragglers in the herd. Most of the time you’re avoiding bad situations by simply looking like you know what you’re doing. I’m not talking about miming being a badass or walking around like you’ve got an attitude—everyone can see right through that (except maybe people you never needed to worry about in the first place). If you end up around truly desperate people the scary ones aren’t the jumpy, theatrically hardcore types. They’re putting on an act the same way many prey animals try to look like predators in nature (there’s a kind of caterpillar that has eyes on its butt so it looks like a small snake, for example). No, the scariest people are the calm, quiet ones. Why are they so calm? Because they know they’re apex predators. Nothing hunts them, so why worry?

What about that weird middle ground, the halfway point between getting sucker-punched and the complete wave-off? We’re back at the party and the guy at the door crosses his arms and simply says, “You’re not leaving.” If you choose violence at this point, is there a best way to get into it?

As detailed above, the best way is NOW. You can throw out all pretense and concepts of technique and simply go for your target. Any defensive moves on his part are moot as long as you don’t play that game—if you’re going to compete with him, tit-for-tat, strike for block, then, yeah, he stands a chance. If you just wade in to beat him broken, that’s what will happen.

This is why we try to get everyone off of the idea of waiting, looking, and blocking. It’s a sucker’s game. For every two you block, the third one’ll get you. Out of all the video footage of violence I’ve seen, none of it—exactly zero—had anyone “defending themselves” successfully. The successful party was always—every single time—the one who did the beating. Or stabbing. Or whatever. The one doing it got it done. The one trying to stop it got done. Period.

So, if you’re worried about what he’ll do, you’re already on the wrong side of the equation. Instead of worrying, make him do something. Like lie down and hug his shattered knee.

That’s not to say there aren’t some interesting tactical considerations to take in executing an initial strike—there are, and we’ll be looking at them in detail, below—it’s just that they are minor and completely subordinate to the idea of wading in and causing injury first and foremost. Don’t get caught in the trap of “fancy”. Stick with what works because it works. Even if it seems beneath you in its simplicity.

Striking when they’re not looking

Alright, this one’s obvious. Just pick a target and wreck it. But everyone here already knew that.

Striking when they are looking

We’re back at the party. The man is standing between you and the door, thick arms crossed over his barrel chest. He just told you you’re not leaving and now he’s staring right at you, daring you to defy him. We’ll assume that other details of the scenario have led you to believe you are in danger (that’s why you were leaving, after all) and you want to get through him and out the door NOW.

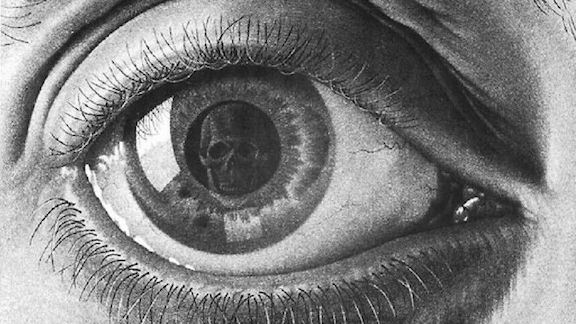

There are two limitations of human vision we can exploit. The first is the fact that when you look straight ahead while standing, you can’t see your own feet. This blind spot is created by the lower part of your face, especially the cheekbones. So he can’t see anything that comes up inside a 45˚ angle off his cheekbones. This is why uppercuts work so well. Any low body shot will work, as well as strikes to the groin using hands/arms or knee/shin. If he’s looking you in the eye, he won’t see the boot to the groin until it’s too late. And here’s where we get into some advanced targeting because if you look down at his groin before you strike him, you’ll tip him off. Your targeting needs to be good enough that you know how to triangulate your foot into his groin based on where you can see his head is. (This ability grows from consistent of mat time with another human body, striking targets in all kinds of orientations. In the end you’ll know the human body as a mass of related targets so well that if you know where one part is, you can strike any other target you wish, without having to see it. This is why we push getting a reaction partner and hitting the mats regularly. This skill is a natural byproduct of that work.)

The second limitation of human vision has to do with the fact that we are predators. There are specific receptors in your eyes to detect motion across a static background. There’s wetware in your head that is specifically wired into these receptors to gage rate of travel and predict where the motion is going. What this means is that if you throw a big roundhouse motion, like a cowboy-style haymaker or other large overhand motion that breaks your silhouette and travels across the static background behind you, every human being on the planet is hardwired to see it, clock it, and intercept it. In the old days it would be to hit a bird with a stick; today it could be for him to simply get his hands up over his face and muck up your strike.

(As a side note, this is one reason people get killed by trains. It is incredibly difficult for us to judge the speed of something when it’s coming head-on. Laterally, across a static background, and we peg it. Coming straight at us, we’re not so good at. People walking on the tracks routinely misjudge the amount of time they have until the train is upon them—and the error typically kills them.)

So if he’s looking at you, don’t break your silhouette—use straight moves that go into the target from inside your outline. Stepping in and driving your fist into his solar plexus with your elbow in nice and tight at your hip fills the bill.

As an example of manipulating both limitations, look at a claw to the eyes. It should come up from underneath his vision and inside your silhouette, not from the far outside like an openhand slap.

And just to reiterate the Important Stuff:

It doesn’t matter if he knows it’s coming or not—get him.

Trying to play this like chess at 90 miles-per-hour will get you hit by the freight train of violence and send game pieces flying everywhere.

It’s not a game, so don’t try to play it.

Injure him NOW.

Manipulating social conventions

This is even more morally problematic, as we are now delving into the use of social tools to maneuver people into position for asocial opportunity. This is what the top-end, most cunning sociopaths are very, very good at—like the American mass-murderer Ted Bundy, for example. Everyone who met him said he was singularly charming; he typically used contrived social devices to lure victims into range (wearing a fake cast on his arm, or walking on crutches).

This may be morally rough ground we’re on at this point, but the misuse of social tools is brutally effective.

The most basic use would be the “false capitulation”. This is where you pretend to give up to get an opportunity to injure him. It can be everything from talking to him, “It’s cool,” or “Okay, you got me, I give up,” to simple body language, palms up, arms spread. Or a combination of the two to get you in close enough to strike while getting him to let his proverbial guard down. I know people who have done this, and it works great.

You can also talk to him to get him to look away. Ask a question and point, and as he looks, drop him. It’s a popular tactic of muggers to approach their victim and ask what time it is—when the victim looks down at their watch, the mugger strikes, having manipulated the situation to gain surprise.

A more advanced, and insidious, version is using your social tools to befriend him. Get him to close distance to shake hands. Then break him.

Of course, the big question on everyone’s mind right now is, “How can I keep from getting taken by these tricks?” The big one is to trust your gut†—people trying to hide something look like they have something to hide. This may manifest itself as small, consciously undetectable tells that you will pick up unconsciously. Your unconscious will then attempt to communicate with you by giving you a “gut reaction”—queasiness, butterflies, or other uneasiness. Trust your gut and act on it. Ask questions later.

To wrap up, there are some interesting tactical considerations you can exploit when going in first—when the situation is teetering on the razor’s edge between social and full-blown asocial. You can exploit the limitations of human vision to “hide” a strike and you can use social tools to manipulate people to your advantage—getting them to move, look away, or disregard you as a threat.

But all of these things pale in comparison to wading in NOW and injuring him. If he knows it’s coming and can see it’s coming that awareness will only work in his favor if you’re playing by the rules—if you are in competition mode. Then it will be a tit-for-tat exchange. If you wade in simply to beat him toothless and witless, then that’s what’s going to happen—whether he saw it coming or not.

— Chris Ranck-Buhr (from 2006)

†And the hair on the back of your neck (or forearms). Piloerection—hair standing on end—is an unconscious threat response left over from when we were much hairier animals. This response is the result of ancient, unconscious brain structures recognizing a threat and attempting to make you look bigger, like a startled house cat.