It’s about what works & survival. Period.

I was recently reading an article on “self-defense” in which the author was speaking of violence as if you could pick and choose the level of seriousness of the interaction, e.g., if they just want to “kick your ass” you kick their ass back, not really hurting them, but teaching them a lesson. If they’re a little more serious, then so are you—and if they want to kill you, well, that’s the only time you’re going to use certain serious techniques and targets like eyes, throat, and so on.

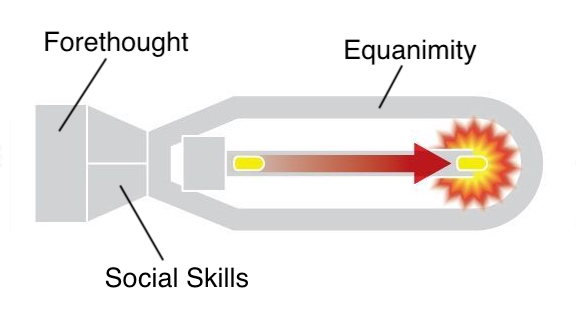

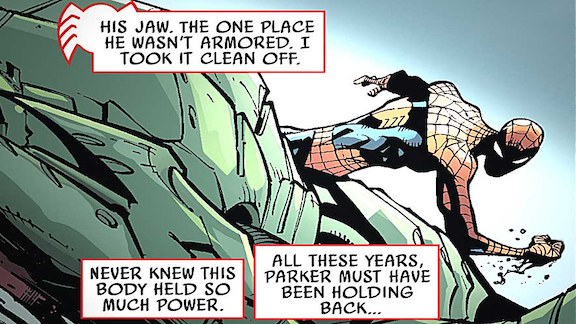

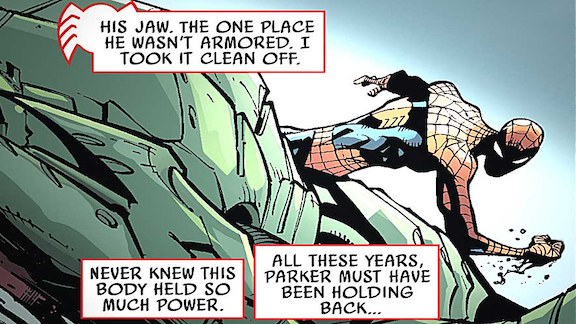

This idea illustrates a fantasy disconnect between fighting and violence, one that deserves a fantasy name: I like to refer to it as “dialing in your Spidey-power.” (With apologies to Stan Lee & Steve Ditko.) It’s the idea that you can choose to hit someone with, say, 60% of what you’ve got—and that you’ll only ever hit someone with 100% when your life depends on it. It’s being able to look at an impending “fight” and say, “Well, they’re not really serious, so I’ll dial my Spidey-power down to 50%,” and then sock them hard, but not too hard, because, after all, you don’t want to kill them, right?

Here’s the problem: holding back can get you killed. There are many ways to hold back:

1) You can wait and see to try and suss out what their intentions are,

2) You can make certain targets off limits because wrecking them is awful (you’ll never hear me say otherwise)—like the eyes or breaking a knee, both permanent, crippling disabilities, and/or

3) You can “go easy” on them by not striking as hard as you can.

Any one of these leads directly to reduced effectiveness, poor results, and in the worst case, can get you killed.

The idea that you can suss out their intentions is a fantastical delusion. If you don’t have psychic powers (and my guess is… wait for it… you don’t) or know the evil that lurks in the hearts of men like the Shadow does, then you’re screwed. You’ll know they want to kill you because, well, they’re busy doing it. That is not the time to find out. In fact, it’s never a good time to find out, right?

Making targets off limits ahead of time (“I’ll never go after the eyes,”) will give you a hesitating hiccup if your next—and only—opportunity is that target. You will stop. And try to get restarted. If you’re lucky, it means nothing. If you’re unlucky, the opportunity is gone and you just got stabbed/shot/whatever (perhaps again) and you just better hope they got it wrong, too.

You always want to strike as hard as you can. Always—as hard as you can. “Holding back” reduces the chance of injury. Now we’re into the realm of slapping each other around, pissing people off, and delivering nonspecific, superficial trauma that is neither a persistent disability nor spinal reflex-inducing. It’s wasted motion that lets them know it’s on.

The author did believe, however, that in a real worst-case scenario a magical transformation would occur—that even though you’d been neutering and watering down your training by waiting, making targets off limits and slapping at them, you could suddenly rise to the occasion of your impending murder by crushing the throat or tearing out an eye with full force and effort.

That’s a neat idea, but it flies in the face of “you do what you train.”

So, to that point, how does the way we train serve you? It would seem, on the surface, that we onlytrain for the worst-case scenario, that to use what you know in any other situation would be like using dynamite to open your car door.

Let’s put it this way: the “worst-case scenario” encompasses and includes all other possible scenarios; going in purely to cause serious injury, put the person down and then pile it on (e.g., start kicking a “helpless” person on the ground) covers, handles, and takes care of anything and everything they may have wanted to do to you.

But the real beauty is that you can stop at any time. You’ll typically do this the moment you recognize that they’re nonfunctional. Let’s say you start out by breaking their jaw at the TMJ. You get the minimum expected reaction—they turn slightly, somehow keeping their feet. You come back with a shot to the groin and get a HUGE reaction, they go down face-first and try to curl up into a fetal position. You break their ribs and then strike to the side of their neck, knocking them unconscious. At this point you recognize that they are nonfunctional (to your satisfaction) and stop.

(Notice that I didn’t mention any techniques or tools—that’s because they don’t matter. Results matter.)

This sequence could have been different at each node of injury—you break their jaw and they spin around three times and lie down, out cold; you stop when they go fetal after the groin strike; you stop after breaking the ribs because as far as you’re concerned, your read on them is “done.” You also know how to carry it to a more final conclusion with a stomp to the neck or throat. But always as an informed choice—not out of desperation, and not after having been trained that it is “wrong” or morally less-than.

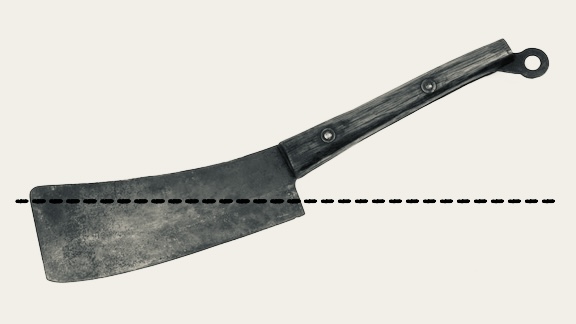

You also know how to start right off with the eyes, throat, or a broken neck—but again, as a conscious choice. If killing is what will see you through, you will kill them. If killing is not appropriate, you can still operate because you know where the line is. This is because you are trained in the totality of violence, understanding it for what it is—a single-use tool that does not have an intensity dial on it. You can’t make guns shoot “nice.” And what a bullet does is the purest expression of everything we’re ever talking about. All violence is the same.

So, what does this mean for you?

First and foremost, it means you understand that violence is not a plaything—you won’t goof off with it any more than you would with a loaded firearm. This is healthy. It means you won’t get sucked into stupid (antisocial) shenanigans thinking you can use what you know without any negative repercussions. It means you’re going to be smarter about when to pull it out and use it. This is going to save you tons of wear and tear, not to mention legal troubles.

It means that when you do use it, you’re going to use it the only way you can be sure it works—with no artificial social governors restricting what you can and can’t do. You’ll strike them as hard as you can to cause injury. And you’ll take full advantage of that injury, replicating it into nonfunctionality.

If we view this through a social lens it is savage, brutal, dirty, unfair, and very probably illegal somewhere. This was the essential thesis of the self-defense author. But the question you have to ask yourself is are you going to bet your life the other person is playing by the rules? If they are, well, then you’re a jerk, aren’t you? If they aren’t, you’re dead.

The moral of the story? Screw around with hand-to-hand violence the same way you’d screw around with a firearm—don’t.

— Chris Ranck-Buhr (from 2006)