For want of an injury, the solution was lost.

For want of a solution, the intent was lost.

For want of intent, the initiation was lost.

For want of initiation, the target was lost.

For want of a target, the body was lost.

For want of a body, the mind was lost.

For want of a mind, the life was lost.

All for the want of actionable information… a life was unnecessarily lost.

An instructor in our program, knowing that I grew up a block from the ocean and still enjoyed beach culture daily, sent me an e-mail about a harrowing experience he and his wife had endured earlier that day while vacationing on the gulf coast of Texas. As a hurricane blew somewhere far off in the gulf, they waded in chest-deep water along the beach, unaware that the leading edge of the storm had kicked up enough wind energy to generate rough waves. The two quickly found themselves swimming for their lives—along with “Mr. Luck”—just reaching the beach before being overcome by exhaustion. “Luckily, I’m a really strong swimmer,” he said, “but what the heck do you do in a rip current?”

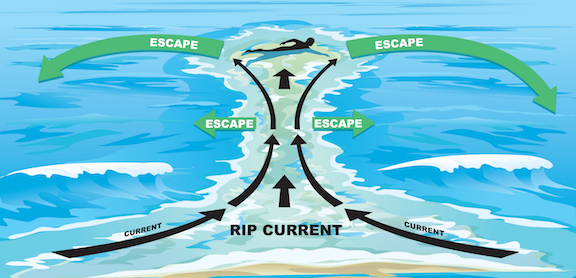

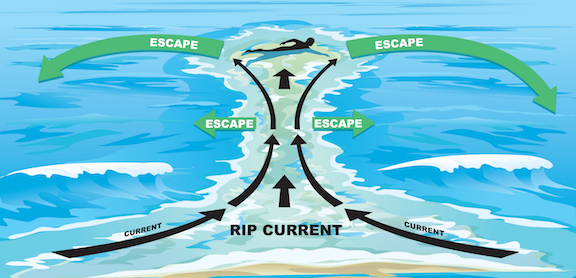

An ocean rip current is a relatively strong, narrow current that flows outward from the beach through the surf zone, and may present a hazard to swimmers. A lack of actionable information about rip currents can, and often does, lead to the death of untrained swimmers, barring the intervention of Mr. Luck. Just a tiny bit of immediately useful information, however, can mean the difference between life and death.

My reply e-mail was brief. What he needed was actionable information. He had some skills and data, primarily the ability to swim hard enough and long enough and the resolve to not give up or panic in the face of impending doom. Mr. Luck was also with him that day. The current could have been stronger, the waves bigger or more consistent, his wife could have given up or dragged him under, either of them could’ve swallowed sea water or succumbed to panic. I could go on… “Swimming and not giving up” was not actionable information under the circumstances. He needed something more. The points I included in the short paragraph described how rip currents work and what to do if you find yourself in the middle of one. I included an image from the National Weather Service that illustrated, in the simplest terms, rip current survival. I then told him his experience was a textbook example of what not to do. If you don’t know, well, you don’t know. I described the variables involved with engaging different wave action, as well the basic solution for a rip current:

1) Relax.

2) Swim parallel to the shore until you are out of the current.

3) Then swim to shore.

In life-threatening emergency situations, your survival depends heavily on the amount of actionable information that you possess inside your mind and your skeleton, and the degree to which the gods have sprinkled “luck dust” on your corpus. In moments of high stress and/or danger, your chances of survival increase if you focus on what you can control rather than what you cannot. Said another way, luck is a poor strategy in these situations.

If the solution to the emergency requires actionable information, then having no information prevents intentional action no matter how much you desire to act. Thus, you are likely to respond with useless or even disadvantageous action, like freezing up or actively working against your survival. If you don’t know what you are doing, doing so intentionally becomes, by definition, a nonstarter.

Further, if you cannot intentionally do something because you don’t know what that thing is, initiating the relevant action to begin the process of intentionally going after the required solution is like… trying to catch a train that’s already left the station. The failure to initiate what you don’t know leads to a catastrophic tipping of things out of your favor. And emergency situations, by definition, have a ticking-clock component: hesitation kills. That first missing piece—a lack of information—is the opening for a cascade of catastrophic results.

Enter luck. If you are “lucky,” the situation just rattles you with the horror of how bad things could have gone. If you are not lucky, the result is a chain of events that rapidly slips out of your control and into a catastrophic death spiral, irrecoverable and non-survivable. You are unnecessarily overcome by the situation for want of a little actionable information… and not quite enough luck this time.

Knowledge is power that is enhanced through experience. For the first-timer, a rip current presents unimaginable feelings of terror and hopelessness. And I highly doubt that the instructor (who barely survived his first experience) wanted to frolic anywhere near a rip current ever again… But if you’re an avid surfer, the rip current becomes just another datapoint in your decision-making process: sometimes you can use the rip to help get through the waves; sometimes the rip can make or break a particular wave. And sometimes you can get stuck in a rip and almost die despite all your knowledge and experience.

It’s important to understand that your knowledge and experience does not immunize you from the power of the ocean. Many big waver surfers have drowned pursuing their passion in situations where they had survived hundreds of times before. Yes, Mr. Luck is a big wave surfer, too. Even small wave riders have lost their lives in “normal” surf. I almost drowned less than ten feet from the shore in Hawaii, after breaking my leash and losing my board, and then trying to swim against a rip while navigating which four-foot wall of whitewater I was going to let rake me up the razor-sharp lava “beach.” Knowledge and experience give you a higher probability of success in an emergency, not a hall pass.

A few days later, I received a second e-mail from the instructor. While walking along the same beach, he and his wife were approached by a young boy in an absolute panic pointing into the stormy surf and screaming to help save his parents. With just his limited experience with rip currents (one horrific, uninformed, and damn lucky go) and the short paragraph of actionable information, the instructor swam directly out into the rip current that had almost killed him days earlier and, following procedure, swam the mother safely to shore. Unfortunately for the family, Mr. Luck got tired of waiting for the instructor to go back out and decided not to stay with the father long enough for the instructor to reach him in time.

So… what does any of this have to do with criminal violence?

In a criminally violent encounter, the first person to impart traumatic injury so that the other person cannot continue wins. If you didn’t know this fact, you’re swimming in that rip current right along with the instructor, his wife, and good old Mr. Luck. For want of a solution, intentional action evaporates. Frozen or flailing, you’ve got nothing useful. Like swimming against the tide, the injuries you receive progressively stack against your survival as your body fails and your mind fades shortly behind. You’re a statistic.

However, if you know this reality about criminally violent encounters, actionable information would include:

1) How the human machine breaks.

2) How to do that work with your bare hands.

3) How to take advantage of the results.

This would provide a solution that you could intentionally initiate, driving you forward to break one thing, and then another, until the other person stops moving or can’t continue. Now you’re a better statistic.

As is true with the rip current, surviving a violent encounter requires knowledge that is enhanced by experience. Let’s say you don’t live near any beaches, but you like visiting them, or you’re about to take an open ocean cruise. In both of these cases a two-day, all-inclusive educational course on open ocean and rough water swimming would be just the thing, where you could get hands-on experience from professionals who have spent their lives not only teaching the material but training the material week in and week out. Moreover, you would want these educators to be invested in your successful understanding of the material. The next best thing would be a one-day course that hit the basic principles and targeted your specific need to understand rip currents so you could enjoy all beaches…

This is what we do—and what we can do for you—when it comes to the use of violence as a survival tool.

— Matt Suitor