Experienced instructors are some of the most relaxed people I know.

The question, of course, is why?

When you have the mechanical ability to cause injury and couple it with the driving motivator of intent, everything throttles back and gets calm and easy—you’re not out spoiling for a fight or giving yourself an anxiety disorder by obsessing violently over every human being who brushes up against you.

This is what I was getting at in “Scenario-Based Training vs. The Hard Knot”. You simply cultivate the skill, and the will to use it, and then sit back and relax into the rest of your life. Should the need arise, you pull out the knot and brain people with it. Then you tuck it back where it belongs and get on with living. (I should note that I’m not talking about a ball of twine here—in my mind it’s an infinitely folded tessellation of agony, a world-heavy, fist-sized sphere from which no light can escape.) You don’t walk around brandishing it high over your head, mad-dogging all comers with a halo of purple lightning dancing about your enraged features. You tuck it behind a smile.

Without intent, without the implacable will to wield the knot, it’s not much better than yoga. Physically challenging, yes. A survival skill, no. (As an aside, it’s critically important to note that the criminal sociopath has very little training—a deficit they more than make up for with vast, raging reservoirs of intent.) So why do people have such a hard time with intent? And most importantly, what can you do about it?

People have a hard time with intent for a number of reasons: They suffer from a natural disinclination toward violence, they worry about what the other person will do, and they think violence is mechanically difficult.

The natural disinclination toward violence

Not wanting to physically hurt people is healthy and sane—but ultimately an impediment to survival when someone poses the question to which violence is the answer.

You need to get over the idea that anything we’re up to here is social in nature. This is why it’s so critically important that your mat time is as asocial as possible—no talking, no nervous laughter, no checking your partner’s face for feedback. The only time you should be looking at a face is if you’re taking an eye out of it.

I’m not talking about getting fired up and hating your partner. I’m talking about dispassion. Lose the emotional triggers—you’re not here to communicate, and raging at your partner (or their targets) is still communication. If you’re working with your “war face” you’ve kicked the social but are busy reinforcing the antisocial. What you really need is to get off the any-social, and get to its absence. That voidspace is the psychic storage shed for the knot.

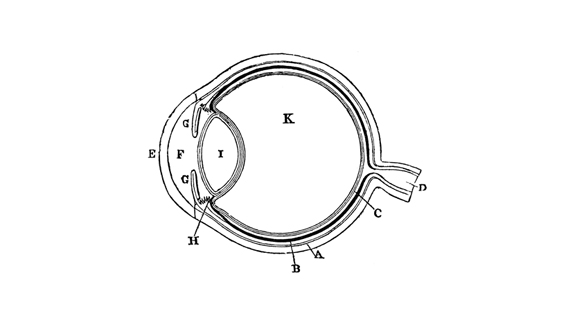

Worried about what the other person will do

Let’s be blunt: Injured people are helpless. Ask anyone who’s done it. The first injury converts a functional person into a gagging meat-sack. Every injury after that is like busting apart a side of beef with your boot heels. This is why experienced instructors are so damned relaxed (and courteous, for that matter). This is also why they won’t hesitate to be the first one doing it. (It’s the ugly truth that no one wants to talk about—how people really respond to serious injury, about how when you cause one, you’ll know it because what you see next will stick to the inside of your eyelids for the rest of your life.)

What is the other person going to do? They’re going to break and behave like an injured person. They’re going to go to the worst place they’ve ever been. And you’re going to put them there.

The question you have to ask yourself is, will you worry about what they’re going to do, or will you make them worry about what you’re going to do? (Hint: pick the one where you’re in charge.)

On this same topic, you need to get off the whole “attacker/defender” merry-go-round. In any violent conflict there’s going to be, by definition, at least one person doing it to another. Be that one person. Decide it’s you, now, and every time after now. Out there it’s always your turn. If you must think in terms of there being an attacker, then it’s you.

Choosing to put yourself in second place is not the best strategy for a win, no matter how much we may venerate the underdog. In a “fair fight” or a contest, the underdog is the hero. In violence, they’re dead.

Quit empathizing with the dead person. You’re doing it because you’re nice, you’re doing it because you’re sane. In a social context, it makes perfect sense. In violent conflict your social skills and mores do nothing but prevent you from surviving. Empathizing with the dead person at the funeral is sane and normal. Empathizing with them while we’re all trying to decide who the dead person is going to be means you’re it.

Bottom line: decide who has the problem—is it you, or is it them?

Believing violence is mechanically difficult

Outside of the psychosocial issues, violence is really, really easy. We’re all predators, we’re all physically built for killing. Violence is as easy as going from where you are to where the other person is and breaking something important inside of them. The rest is academic.

How easy is it? General consensus says easier than free practice. You get to strike as hard as you can, follow all the way through on everything, you don’t have to take care of them, and it’s over so fast you won’t even have time to break a sweat or even breathe hard. The only hard part is giving yourself the permission to be inhumanly brutal, giving yourself the permission to survive. (I recommend you vote for you every time.)

Thinking that violence is mechanically difficult (and thereby trying to give yourself an out so you don’t have to face your own intent problems) is akin to thinking that swimming in the deep end is any different from swimming in the shallow end. Mechanically, it’s the same—swimming is swimming—the difference is all in your perception. In the shallow end, you can touch bottom and can save yourself from drowning by standing up. In the deep end you’re on your own—it’s sink or swim. So everyone thinks free practice is the shallow end; there’s no risk, you can always “stand up” when you get into trouble. That would make the street the deep end—no backup, no safety net, just swim or die. I’ll grant all of that as true. Just remember, always, that no matter where you’re swimming, mechanically it’s all the same. The idea that there’s a difference is an illusion that takes effort on your part to make a reality. Stop feeding the phantoms and just swim.

Intent—your will to cause injury, your drive to get it done—is completely up to you. You need to start thinking about it now, personally letting go of the things you’ve kept between the “you” you love because they’re a lovable, good person, and the “you” that can stomp the throats of screaming men.

We can only show you how to mechanically take someone apart—pulling the trigger on it is up to you, and you alone.

— Chris Ranck-Buhr (from 2006)