Tactical Cruelty

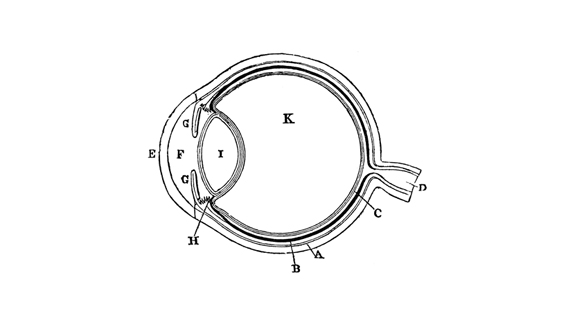

“Violence is the race for the eye.”

— Master Derrick Farwell

When he was a young Marine, Derrick sought effective hand-to-hand combat training, going where stories of ass-kicking and dread reputation led. One night he ended up in a dingy karate studio; the instructor was a Vietnam-era Marine from Okinawa, a compact, no-nonsense man versed in the stunning language of fists and feet. That same night a much larger, and thoroughly drunk man, came in and challenged the instructor to a fight in front of his students. The instructor demurred, and tried to get the man to leave. But he would have none of it, and so the instructor took him up on his offer with a blow to the solar plexus. They folded to the ground and began rolling, rolling, until suddenly the larger man screamed, leaped to his feet and fled the school with his hands pressed to his face. Meanwhile, below the look of grim satisfaction, the instructor’s gi was spattered with the big man’s blood.

Derrick credits this moment as a turning point in his training — not because he learned some cool new “go-to” move or an inspirational Bruce Lee quote — but because of a simple truth: the one who gets it right first wins. It’s not what you think you know or how you look doing it — what happened inside that ball of chaos didn’t remotely resemble a magazine photoshoot karate technique — it was a mess, figuratively and literally. But it was a mess that made a difference.

From that moment on Derrick would only listen to instructors whose training was a physical reflection of that awful truth.

This is why we will always speak plainly about our work — training people to use violence as a survival tool — and not waste anyone’s time with the expected and socially acceptable euphemisms of self-defense, self-protection, etc., etc. (Euphemisms that impose a potentially lethal drag on the needs of action. All language surrounding a thing tells the story of where you see yourself in that thing. Ask yourself: During your attempted murder, do you want to “defend yourself” or “attack and injure”?) We seek to communicate with those who know or sense this truth, and who feel something vital is missing in their current physical application.

It’s one thing to say, “When things get serious, go for the eye,” and another to spend every mat session doing what those words actually mean. We set foot on the mats assuming we’re already at maximum “serious” — we get straight to it… and make sure the blind man gets a broken leg and a head injury for good measure. Violence isn’t a contest or a game, and we assume the loser gets set on fire.

Training like this has two effects on behavior:

1. We will do everything in our power to avoid violence if we have a choice, and

2. We will do everything in our power to finish it first if we don’t.

If violence is the race for the eye, we’re going to cheat by starting at the finish line. Anything less is betting your life that the other person is nicer than you are.

— Chris Ranck-Buhr

Chris,

After taking a new person training, I was talking with my daughter who was attending a local, well known university. I told her that if any person attempted to attack her, bury her thumb as deeply as possible in the attacker’s eye. She asked a few questions, but seemed to give the typical teenage noncommittal response. Several months later, I find out she actually had to do this as she was attacked on campus. She said the attack stopped immediately once her thumb was in his eye, all he could think about was how to get the thumb out.

I am so proud of her and glad the results turned out relatively positive for her.

Doug,

Thanks for letting us know—this is, after all, the reason we do what we do.